If your company makes software, it’s probably not hard to find a graybeard in the basement who’s lost all faith in humanity. It is the avowed destiny of every Twittering, eager-eyed college graduate who intends to write software for a living to become a graybeard, whether or not s/he realizes it. (I know the term “graybeard” excludes women, but don’t fret: They too will become graybearded. Despair knows not gender.) There are many reasons why developers lose their souls and become pitiless automatons over time, but chief among these reasons is you. That’s right, you. (And Internet Explorer. And mobile phones. But you, mostly.) In this series, I hope to touch upon a few reasons why you continue to make web developers lives’ miserable and what you can do about it.

Please understand that we (that is, you, the project manager, and I, the web developer) have a common goal, which is to acquire dollar bills. If anyone tells you otherwise, s/he is lying and intends to obtain more of the total available dollar bills than you. In America, we all know dollar bills equal freedom, and freedom equals happiness. Doing whatever you can to not make web developers miserable means they will be more inclined to type things for you we can later trade in for dollar bills.

#3: Assigning New Work Five Minutes Before 5

The work production people do is necessarily at the end of the line. It’s the last thing standing in the way of “done.” In the web design world, these people are principally visual designers and developers. After all your thinking and negotiating and plotting and managing, we have to do the making. We understand you’re under tremendous pressure to get through this last annoying step—where the thing you’ve spent so much time thinking about enters reality—so the client can get what it wants and get off your back. But what you don’t understand is that, from our perspective, everything is only just beginning, especially if we’ve been left out of every ideation session that preceded your telling us it’s go-time. I can’t fuel up a project on exhaust fumes, so even if you are working with negative time, don’t make me suffer for it. I haven’t even done anything yet!

On that note, there’s nothing more infuriating to a developer than to be handed one or two hours of work five minutes before 5 with the ultimatum “this has to be done by the end of the day.” My resentment for you in this situation has nothing to do with my dedication or my ability to be a “team player.” Agreeing to work for 10 hours instead of 8 is called working for free and is not synonymous with being a team player. (It’s synonymous with being a chump.) This is really about negative time: starting a task with less time than is necessary to do a good job.

Now, I grant there are probably many reasons why you might have decided to hand me two hours of work five minutes to 5: maybe you were in meetings all day and couldn’t get it together earlier; maybe you just found out about this five minutes ago; maybe you’ve been working goddamn hard all day to be able to reach a point where you can hand off the work to the production people because if you don’t get something to the client by 10 am on Monday you’re doomed despite the fact that you’ve been on the ball all along and none of this is your fault. Or maybe you just actually suck and have been sitting on it all day. I don’t know. I didn’t choose a project manager’s I’m-a-drunk-who-sleeps-in-the-office-every-other-night lifestyle.

I’m not incentivized in the same way as you are. But I can commiserate, if you treat me like an equal rather than a morlock. I’m not particularly bothered by staying late to deal with your mess if I see you as a person who’s been screwed by forces beyond your control. Some of the most enjoyable hours I’ve spent with project managers were from 5 pm to midnight working on unsolvable problems for which neither of us were responsible. We were not paid overtime, we ate oatmeal and bourbon, we talked about our dreams and aspirations in between uploads, and deep in our bellies we nurtured a profound hatred for the Internet. If you don’t approach me with a sense of compassion, my only takeaway is that you lack respect for my craft and believe that turning out production-quality code with negative time is easy because I am a code monkey. You’re going to get the worst code possible when you ask for it written under the worst circumstances: vengeful, makeshift, lazy. And guess what? That kind of code is buggy and it’s going to implode on itself at 10 am on Monday right before you show it to the client.

#2: Ignoring My Technobabble

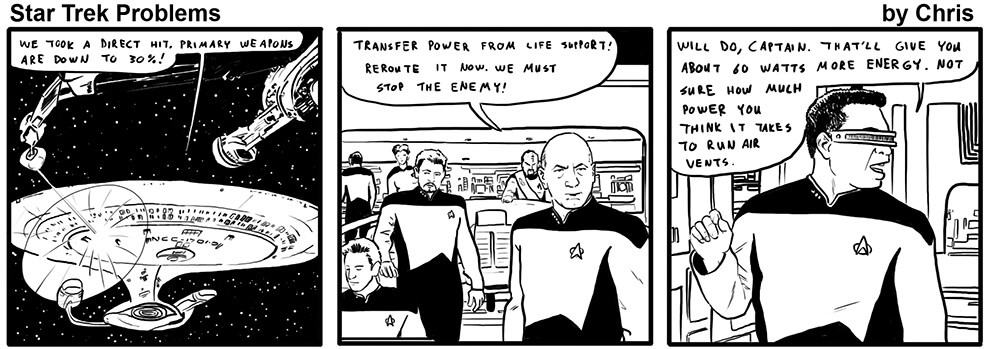

One of the reasons why I love Star Trek is because the technobabble you hear in most episodes isn’t actually technobabble due to all the consulting physicists who worked with the writers of the series. (Well, at least after the Original Series.) If you try to listen to what the engineers are saying in each episode, you may not have any idea what any of it means without reading up on some layman physics, but you will get a sense of how the Enterprise works, at least conceptually, and a better appreciation for the complexity of the Trek universe’s physics.

I also love seeing the captains reduce their engineers’ every estimate to a fraction of what was originally requested. In The Next Generation, when engineering Chief Geordi La Forge asks Captain Picard for 3 weeks to solve a problem, he usually gets three days or three hours. Of course, La Forge’s inevitable success is supposed to be a testament to his ingenuity in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, not an example of the Chief’s gross overestimation of the length of time it takes for him to solve a problem.

In web design, it’s no different: a good captain can cut an engineer’s estimate down to size based on her faith in the engineer’s ingenuity and her conceptual understanding of the problem. And conceptual understanding is key: a good manager is effective at managing her engineers because s/he listens to them. When an engineer explains what the problem is, you listen, even if you don’t “get” it. You don’t dismiss it as incomprehensible jargon that you don’t need to know. Developers are ornery and don’t volunteer information often because they assume you could care less what’s going on under the hood. But the moment you open up, you’ll be surprised how quickly we open up.

#1: Treating Me Like a Code Monkey

Jaded project managers and jaded developers are prejudiced against each other. When I give you an estimate, you automatically assume that it’s inflated because I’m reserving enough time in my estimate to be lazy, and I automatically assume you’re withholding information when it comes to deadlines. We’re both lying to each other to get the best out of our situations. Whenever I start somewhere new, I invariably have to bust my ass to prove my word is gold to project managers who don’t know me, and it makes me sad to think I’m starting at -50 brownie points rather than 0 just because the rapport between project managers and developers is naturally adversarial.

The problem here is not that either of our assumptions are wrong, per se. You can’t really know that I’m lying until everything is said and done, and vice versa. It takes time and evidence to establish trust (and the only way to determine if someone is trustworthy is to start trusting them). But what you can do in the interim is try to better align our incentives. If we’re both working to get this feature done by Thursday at 6 pm so we can go out for drinks on Friday with nothing but visions of booze hanging over our heads, then it’s no longer you against me: it’s just us working together to get sloshed. In my opinion, there’s no nobler goal than getting sloshed together on a Friday night after work.

The other assumption that particularly irks me is that I’m just a code monkey who doesn’t understand anything except computers. Most web designers I know (whether they’re visual designers or back or front end developers) didn’t start their careers in web design and don’t have academic credentials in computer science. We are illustrators, theater geeks, creative writers, videographers, and philosophy majors. Some of us have graduate degrees in unrelated fields, and others have no real passion for web design, we just do it for the paycheck. It’s possible some of us got into the field totally by accident (myself) or we don’t even touch a computer when we get home (one particularly brilliant Javascript developer I know). You have no idea what we’re like outside of what we type on our computer screens, so don’t assume we’re incapable of generating creativity or understanding the strategy challenges you grapple with every day. Trust me, we don’t want to go anywhere near a Gantt chart, so the better we understand we each other, the faster we can help each other get our respective jobs done.